Yesterday, August 14th, was the 65th anniversary of the end of World War II. Prior to the start of the US involvement in WWII, the Army and Navy had been intercepting and decrypting radio messages between Japanese military units, consulates, embassies, and other overseas locations.

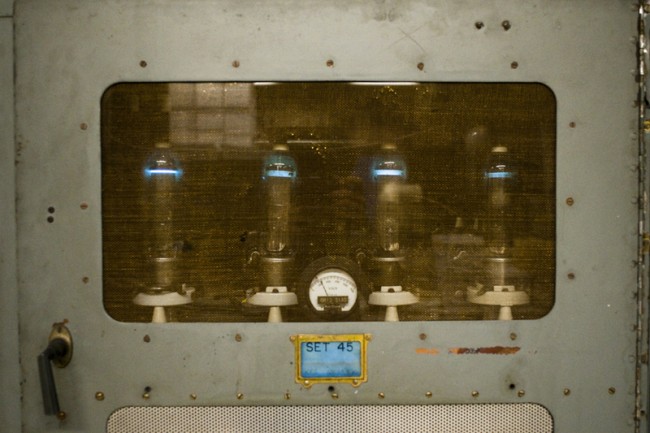

Back in the day, most everything was sent via Morse code over HF radio circuits. It was the fastest way to send information from one point to the next. These messages would be encrypted offline, either by hand or by a special typewriter. The message text would then be altered into 5-number, seemingly random, groups. On the other side, they would be deciphered using a key that matched the enciphering key. There were several different ciphers systems being used, some for diplomatic traffic, several others for military, merchant marine, etc.

Since the messages were transmitted via radio, they were easy to intercept. Everyone knew that the other side was listening. The Japanese assumed that their codes were secure because a “Caucasian mind could not possibly unravel the intricacies of a Japanese code.” An assumption the Navy cryptanalysts had different ideas about. Through the 1930s and early 1940s they broke some of these codes, but not all of them.

The Japanese diplomatic code was called “purple” by the US cryptanalysts. It relied on a machine called System 97 (by the Japanese) which used telephone stepper relays to generate an ever-changing stream of random code groups. It was considered too secure to break. William Friedman, a mathematician working for the Army, studied the purple messages and deduced that it was a machine-generated code. He then went to work on duplicating the machine and after a year or so came up with a perfect replica of the Japanese System 97 machine in early 1941. From that point on, almost all of Japan’s diplomatic message traffic was being read by the Army, Navy, and state departments. This work was top secret and carried out at the war department in Washington. Information gleaned would be sanitized and transmitted to major commands as needed for tactical intelligence.

In early November 1941, the Japanese foreign office came up with the following code to be transmitted to the embassies in the event of the outbreak of war:

HIGASHI NO KAZE AME (East wind rain) = Japan – US

KITA NO KAZE KUMORI (North wind cloudy)= Japan – USSR

NISHI NO KAZE HARE (West wind clear)= Japan – Britain

It is believed that on either December 4th or 5th, East wind rain message was received and decrypted. This was testified to Congress in 1945 by the head of the Navy COMMINT section, however, no record of the decrypted message exists. Instead, there is a blank page and a missing message number (JD-7001) in the Japanese diplomatic intercepts file.

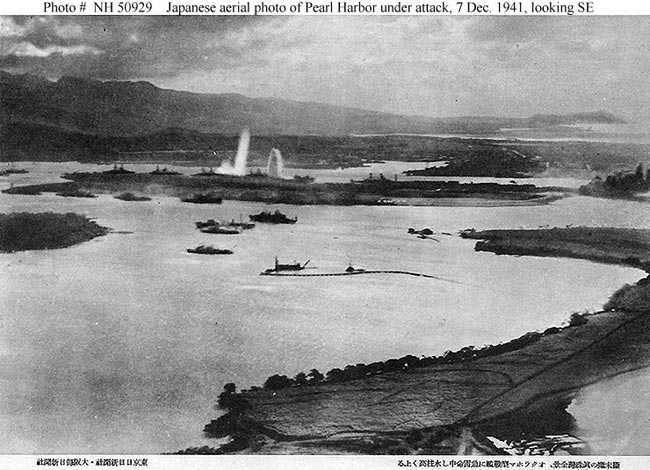

The fleet commander at Pearl Harbor knew none of this, as the information was kept under close wraps by the Navy Department in Washington. In early December 1941, almost everyone figured that war with Japan would happen very soon. Most of the Washington set believed it would start in the Philippines, then a US territory. No figured that the Japanese would steam 3,900 miles undetected and launch a sneak attack on the US military base in Hawaii. The attacking planes homed in on the signal from KGMB (after-war reading of Cmd. Fuchida’s (IJN strike leader) diary indicates the actual station was KGMB on 590 KHz, and not KGU as their website claims), to help find Hawaii from carriers still 230 miles away. The station had remained on the air overnight to assist a group of B-17 navigates from the west coast. Unaware of the impending danger, the Hawaii military bases were enjoying a peaceful Sunday morning until 7:48 am, when the first bombs began to fall.

Of course, had the Japanese pressed the attack and launched a third wave to take out the fuel storage and repair facilities, indeed, history might be different. The Pacific Fleet would have had to retire to California, leaving Hawaii exposed and quite possibly invaded.

Most people on the mainland first heard about the attack via radio. At 2:22 pm Eastern time, the AP issued a news bulletin and at 2:27 pm CBS broke into their Sunday afternoon programming to announce the attack. The radio played an important part in WWII from start to finish.

History geek. You is one.

Welcome to the club.

And at the time prior, Roosevelt knew of Tojo’s plans but waited until immediately after Pearl Harbor to rile up the public for another World War. His “New Deal” hadn’t worked and he needed the banksters of war to spice up the economy. If Wendell Wilke would have been elected in 1940, it is my personal belief we would not have entered the war at this time and just maybe WWII would not have occurred with our attendance at all. If we only had the Internet back then!