In this modern day and age, we take electronic communication for granted. Imagine being plunged into a world where there are no phones, cellphones, internet, email, television, or even radio. Back in the day when I served aboard ships, we called that being underway.

Way, way back in the late 1980s and early 1990s, those that served at sea were at the mercy of the Fleet Post Office. I will say, the FPO did a very good job routing the mail to the appropriate place, however, sometimes weeks or even a month would go by without mail. When the mail finally did arrive, it all smelled the same. Everyone’s wife or girlfriend put some sort of scent on the outgoing, but since those letters mingled tightly packed in the same bag for weeks, often in hot humid tropical Pacific air, those scents blended together and became the Westpac Mail Smell, which permeated everything, even the letters from my father.

What will happen if people can’t sign on to Facebook?

Fortune favors the prepared.

Communications loss in ordinary circumstances

Loss of utility company power, phone service, and internet service can happen at any time for a variety of reasons. The worst case scenario will occur when such loss is coupled with a natural disaster, which is often a major disruption of normal life. Loss of information, especially at critical moments, can make a bad situation much worse. In a situation where all normal means of communication are not functioning, something will fill that void, most likely the rumor mill. That could be bad.

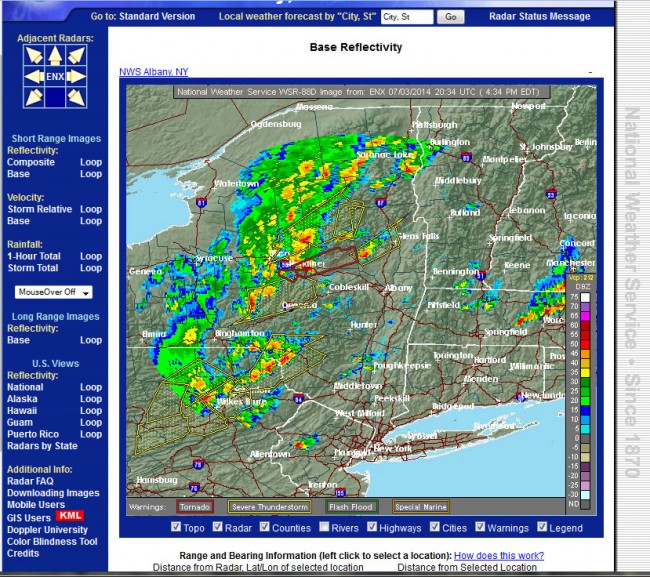

For information gathering, there are many options. A good AM/FM shortwave radio is a decent start. I would recommend a quality shortwave radio that has AM/USB/LSB options. During run-of-the-mill storms and power outages, many radio stations will remain on the air with emergency generators. The key is to figure out which stations are staffed and offer good timely information. NOAA all hazards radio can be a good source of weather information, however, their transmitters can remain off the air for weeks or months at times.

One might ask “Isn’t this overkill or alarmist?” I suppose that depends. In the December 2007 ice storm, we had no power for seven days. In the aftermath of several major Northeast hurricanes and winter storms, some people had no power for more than two weeks. Not only no power but no cable, phone or internet either. In situations like that, having some form of connection to the outside world can make a big difference.

Communications loss in less-than-ordinary situations

Other situations and scenarios may require more effort. Prolonged information shortages could be triggered by any number of national or global situations. Shortwave receivers are not only for listening to international broadcast stations but also for tuning into amateur radio (AKA “Ham”) frequencies as well. Amateur radio is often used for emergency communications on a local and national and international level by governments and the Red Cross when other systems are out. National and international communications are often heard on the HF band; 3-30 MHz. The Amateur radio primary emergency voice nets are:

- 3791.0 USB VOICE PRIMARY International, DX, and Emergency/Disaster Relief

- 5371.5 USB EMERGENCY Emergency/Disaster Relief

- 5403.5 USB EMERGENCY Emergency/Disaster Relief

- 7185.5 USB VOICE PRIMARY International/Regional and Emergency/Disaster Relief

- 14346.0 USB VOICE PRIMARY International/Regional and Emergency/Disaster Relief

- 18117.5 USB VOICE PRIMARY International/Regional and Emergency/Disaster Relief

- 21432.5 USB VOICE PRIMARY International/Regional and Emergency/Disaster Relief

- 24932.0 USB VOICE PRIMARY International/Regional and Emergency/Disaster Relief

- 28312.5 USB VOICE PRIMARY International/Regional and Emergency/Disaster Relief

These are voice channels from the ALE website. If there is no traffic on these frequencies, tune around a little bit. In addition to voice nets, the amateurs also use something called ALE, which stands for automatic link establishment. This is a data system that can be decoded on a listen-only basis with a computer and some free software, for those so inclined.

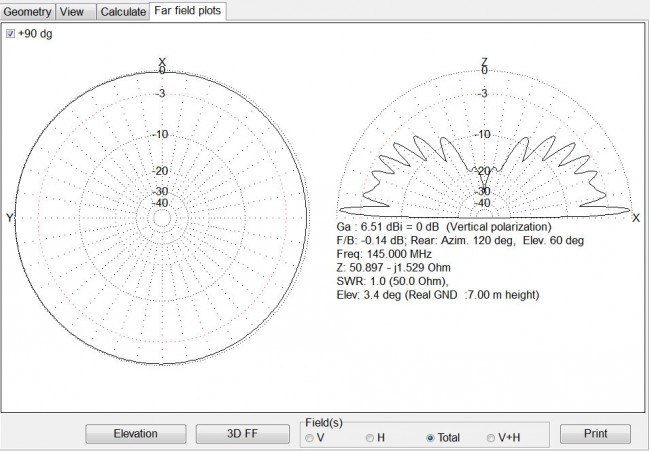

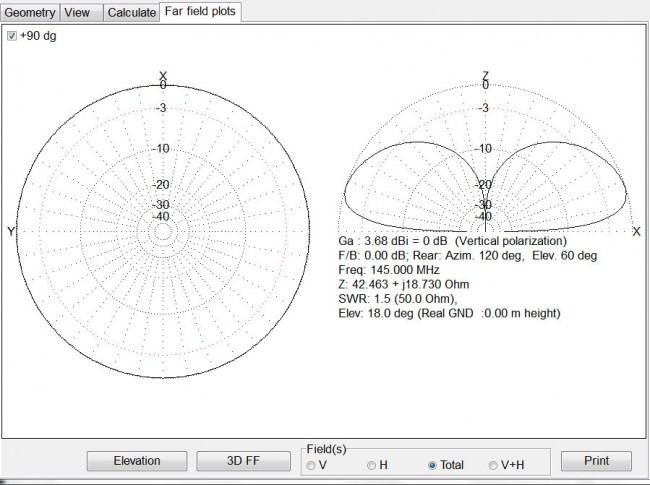

For local amateur communications, 2-meter and 70-cm repeaters are often pressed into service. For those, a VHF/UHF scanner is required. Get a trunking scanner for 800 MHz police/fire dispatch as well. Make sure that all radios can operate on 12 volts DC. For this application, the size of the solar panel and the battery is moderate, as receivers do not use much current.

Another option is a wide-band USB radio for a laptop computer like a WinRadio WR-G315e. These devices can be powered by the USB outlet on the computer while the computer itself is charged with a solar panel. For this route, some research on laptop solar chargers is needed. The DC power requirements vary from laptop to laptop, so I can only offer general advice here.

With any receiver, a good antenna will greatly improve performance. If there is room for an outdoor antenna, any length of wire strung up in a tree, away from power lines will work well. For indoor setups, some type of receiving loop will work best.

Prolonged loss of communications in extraordinary circumstances

For longer-term situations, gaining access to vital information and communications may become more problematic. First of all, electronic communications require electricity. Long-term disruptions to the electrical distribution system could occur by either natural or man-made events. When those events happen, those that are prepared will be in a better position to survive if not thrive. Things like ad hoc computer networks and amateur radio can facilitate two-way communications. In order to use amateur radio, one needs to get a license first. This is a pretty easy thing to do and most other amateur radio operators won’t talk to you without a valid call sign. Not only will they not talk to you, but they will also likely track you down and report you to the FCC. That is the nature of the hobby, like it or don’t.

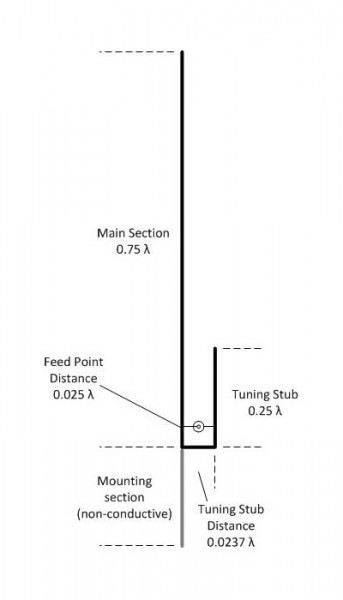

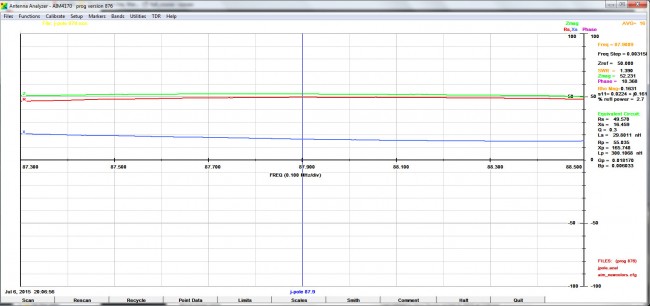

Amateur radio setups can be very simple and not terribly expensive. A used HF radio can be purchased on eBay for a moderate sum. A simple multiband vertical antenna will serve general purposes. For those that are interested in HF Link, a newer radio will work better.

Wireless ad hoc computer networks can be set up to establish a quasi-internet over a moderate-sized area. WiFi WAN networks can be locally established using 900 MHz, 2.4 GHz, 5.8 GHz, and 24 GHz license-free channels. Depending on the frequency, those links can be used for point-to-point medium to long-haul links, or to establish local links to laptops and wireless devices:

- 900 MHz: lower speed data rates, long haul, good to moderate building and vegetation penetration

- 2.4 GHz: Limited channel availability, high atmospheric absorption, moderate speeds, low vegetation, and building penetration

- 5.8 GHz: High number of channels available, potential interference issue with TDWR radar systems, moderate to high speeds, line of sight only

- 24 GHz: Large bandwidth, high speed, point-to-point backhaul, line of sight only

Once the information is obtained, distribution to the greater public becomes a problem. A very simple webserver (Apache, Nginx) with a lightweight, simple index page containing vital information, news, weather, etc can be set up on a laptop and all HTTP traffic is directed to the default index page. This type of setup could be run off of a battery charged by a solar panel. The issue here would be obtaining the information to put on the web page.