The model for Radio Engineering these days is such that one engineer is covering multiple stations in various locations. At the very least, this person has a full (if not overflowing) plate. Thus, when something breaks, the procedure very often is; to pull the suspected module or board, call the manufacturer and order a replacement. That works as long as the manufacturer supports the model in question or has parts. As we all have learned by now, replacement parts are subject to the global supply chain, which is tenuous.

Then there is the question of AM transmitters. Is it worth it to replace an AM transmitter these days? I suggest it would depend on the market and revenue. In some cases, yes. In other cases, keeping the older equipment running makes more sense.

Troubleshooting is becoming a bit of a lost art. In addition to the time it takes, we tend to be unfocused and obsessed with rapid gratification, ready for the next social media post. What is lacking is the ability to take apart the layers of a problem, accept our initial analysis may be flawed, move beyond those assumptions, and work until the issue is solved. Troubleshooting is often like a crime scene investigation. There are several logical steps;

- Assess the current situation; take steps to ensure it is safe to proceed. Remove all power from the transmitter and don’t work on failed transmission equipment during thunderstorms

- Gather evidence; look for fault indicators, alarms, automated log entries, burned components, abnormal meter readings, etc

- Check external factors; power failures, lightning or storm damage, excessive heat, moisture, etc

- Check internal factors; aged components, bad cables or connectors, improperly seated boards or components, and obvious signs of damage

- Work from one side of the issue to the other

- Check the maintenance logs (if there are any) to see if this problem has occurred before and what was the fix

- Use available resources; troubleshooting guides provided in equipment manuals, factory support, and available test equipment

- If a failed component is found, make sure that it is the problem and not a symptom of something else

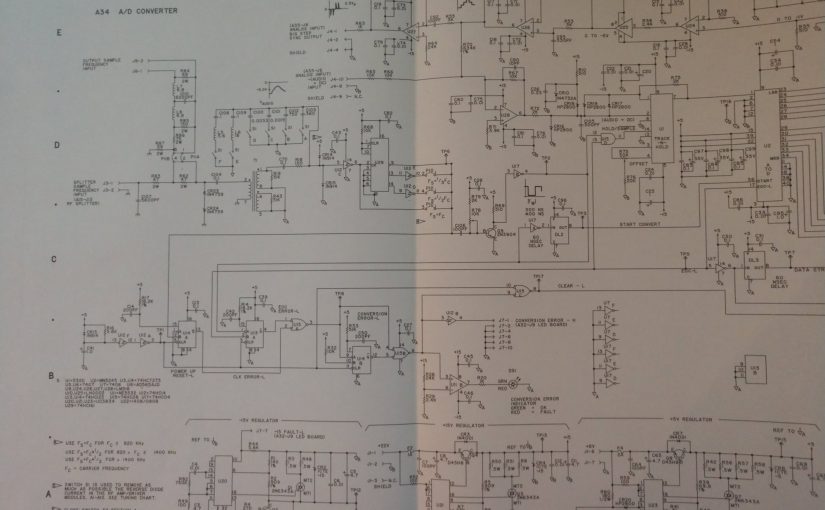

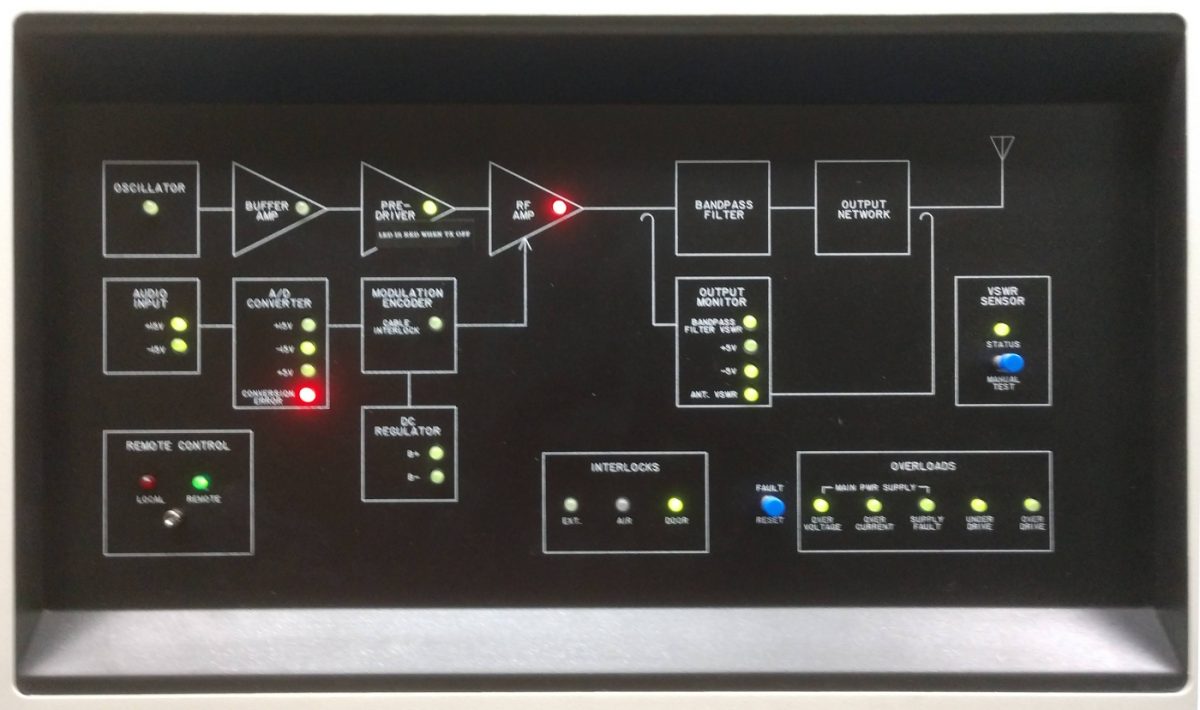

Here is a good example of a recent troubleshooting evolution; I went to change over to transmitter #2 and these fault lights appeared:

The conversion error on the A/D converter indicates why the transmitter power output is zero.

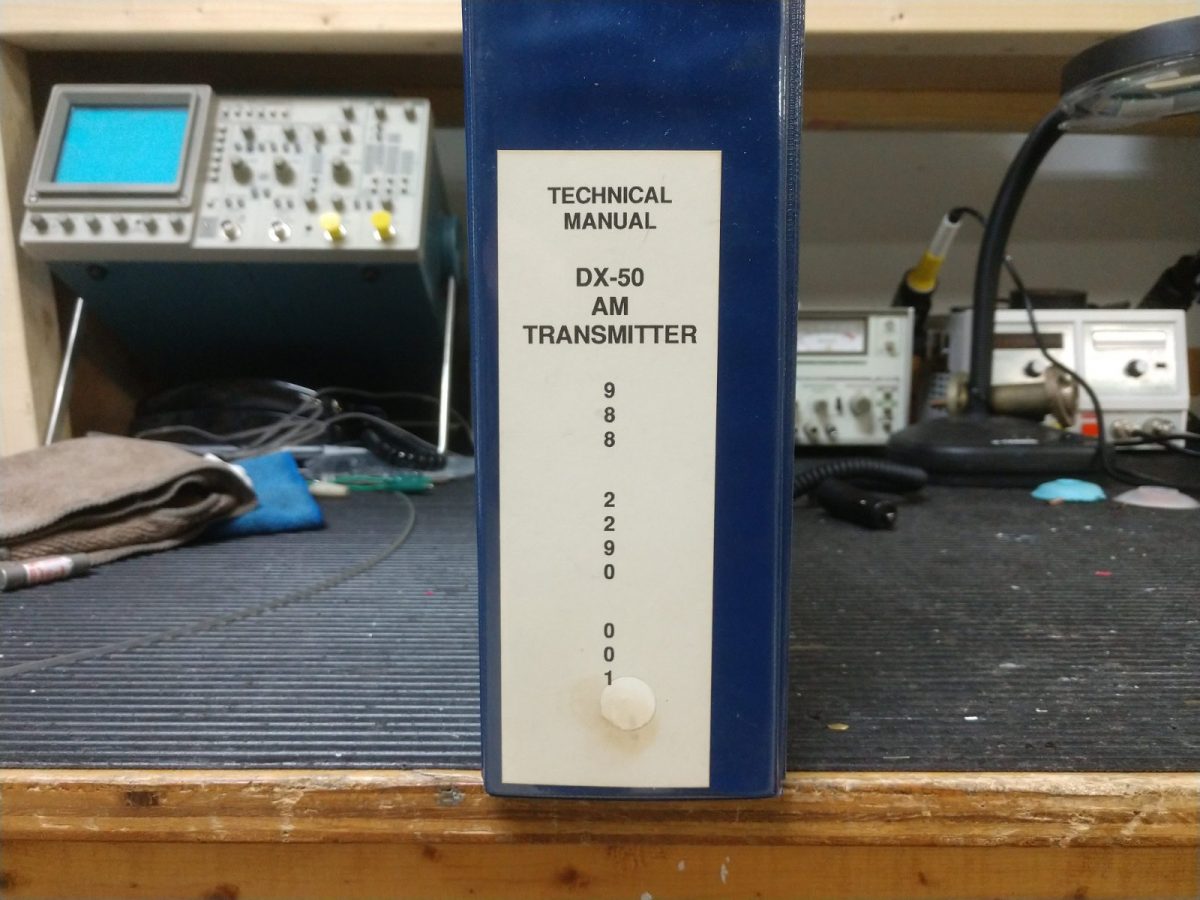

The first step; secure the transmitter, remove all power, etc. Next, consult the book!

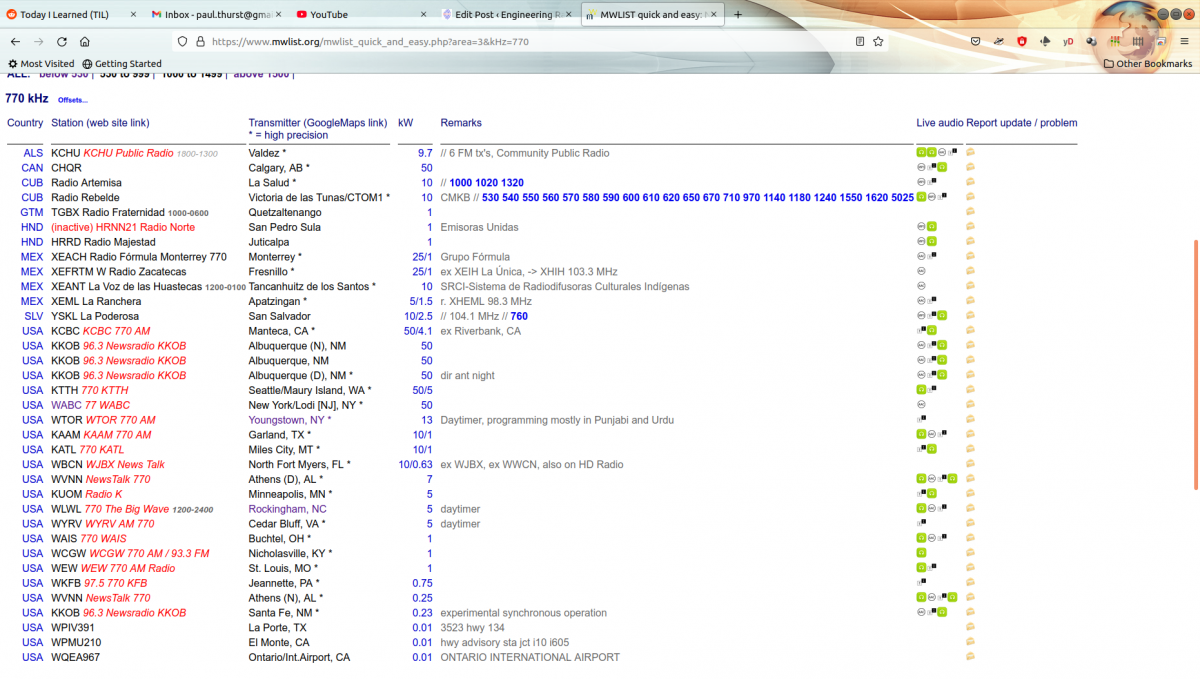

The Harris DX-50 manual gives good troubleshooting guidance. This transmitter was manufactured on March 22, 1990. It has been a reliable unit, to date. Section K.4 Analog to Digital Converter (A34) of the manual suggests loss of audio clock frequency sample due to the following;

- Loose connection with the carrier frequency sample cable coming from the RF drive splitter (A15)

- Bad or missing jumper connections on P-10, frequency divider section

- Bad U-29 (74HC161, 4-bit binary counter, only in use if the carrier frequency is above 820 KHz, Not Applicable)

- Bad U-12 (74HC14, Schmitt trigger)

- Bad CR13 or 14 (1N914)

Fortunately, there was a working DX-50 about 15 feet away, so I was able to make some measurements at various places on the A/D converter board.

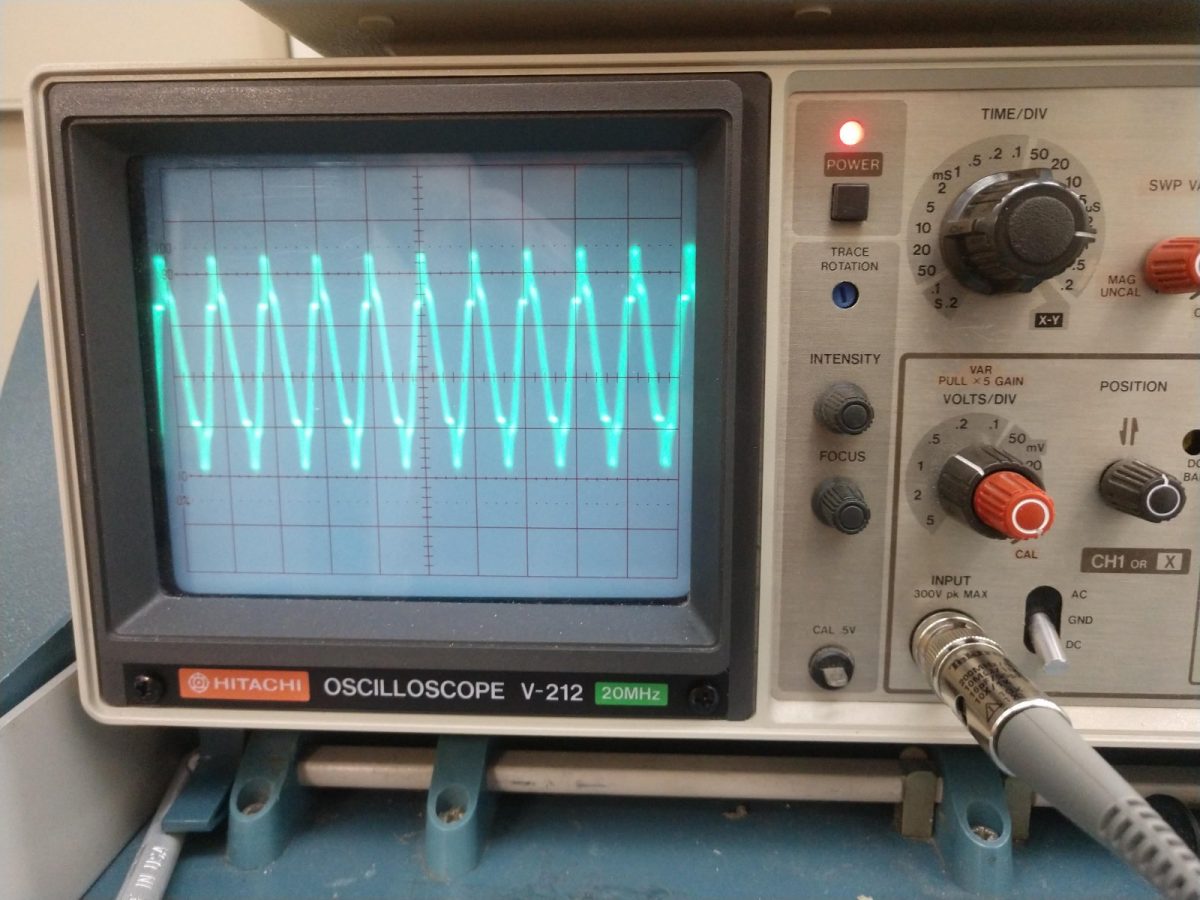

On the working transmitter (DX-50-1), at the RF sample input (input of R83) on the A/D converter board, I see a nice strong sine wave, on frequency:

Second, I measured the logic pulses on TP-6, as described in the manual. Those look good.

On the non-working transmitter, I made the same measurements and found a fuzzy sine wave way off frequency on the input of R83. The logic pulses on TP-6 was normal.

Definitely lost the RF sample. Since the transmitter is 32 years old, I suspected the cable (#92, RG-188 coax) between the RF drive splitter and the A/D converter had gone bad. Perhaps rubbed through on a rough metal edge or something like that. Several checks with a Fluke DVM showed that there were no shorts to ground or internal conductor shorts. End-to-end checks on both the shield and inner conductor proved good. So, not the cable…

I then went on a bit of a wild goose chase suspecting the output from the oscillator to be low or the drive regulator power supply was defective. The drive level going into the PA was close to normal but slightly lower than the previous maintenance log entry. Also, drivers 8A and 8B were both on, which is not normal and made me suspect the drive regulator.

I made a call to GatesAir and spoke with a factory rep, who had me swap out the A/D converter, oscillator, driver power supply regulator board, and the buffer amp/pre-driver module between the working and non-working transmitter (while the low-power aux was on the air). With the working transmitter close by, I was able to confirm that these boards or modules were not the cause.

Finally, I went back to the RF drive splitter and use my camera to take a picture:

There is a 6-pin connector on the underside of the board (J-17). Pin 2 (from the right) is the center conductor and pin 1 is the shield of the cable going to the A/D converter board. Upon closer examination, the solder joint on pin 2 is suspect. I re-heated this connection with a soldering iron and viola, the transmitter started working again.

The extenuating circumstances; the air conditioning at this site was slowly failing and that part of the transmitter was subjected to heat cycling several times. More recently the HVAC system was in the process of being replaced, of course, on one of the hottest days of the year. This pulled a lot of warm, humid air into the room. Also, as this is transmitter #2, it was not in regular use until recently (we began a procedure for operating on alternating transmitters for two-week periods).

All of this work took place over the course of two and a half days or so. That would be a lot of time for the module swap guys who tend to move on to the next outage quickly. On the other hand, buying a new 50 KW AM transmitter is an expensive proposition these days and there are very long lead times on some of these units. Being persistent and focused paid off in the end.