Continued from Part III

Profile of a successful AM radio station, March 2013: WSBS, Great Barrington, Massachusetts

Great Barrington is either a large village or a medium-sized town with a population of approximately 7,100. There are many listenable FM and AM radio stations from Albany, NY, Pittsfield, Springfield, and Poughkeepsie, NY markets. There are also a few local stations; WBCR-LP, WMAQ (WAMC repeater), and W254AU (WFCR repeater). While the competition is not fierce, citizens have a variety of stations to choose from.

WSBS is a class D AM station on 860 KHz with 2,700 watts daytime power, 250 watts critical hours, and 3.9 watts night time power.

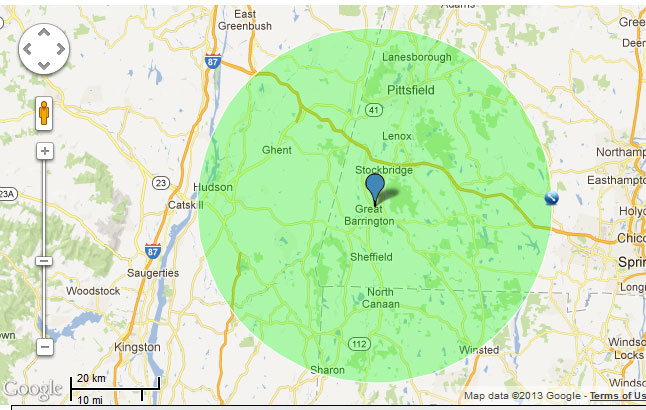

This is the approximate daytime coverage area for WSBS AM. I could not find any good coverage maps online, so I made this one myself. When I am driving, I get the station reliably to Kingston, NY, however, indoor listening may be a different matter. With 3.9 watts ERP, nighttime coverage does not include much of the city of license.

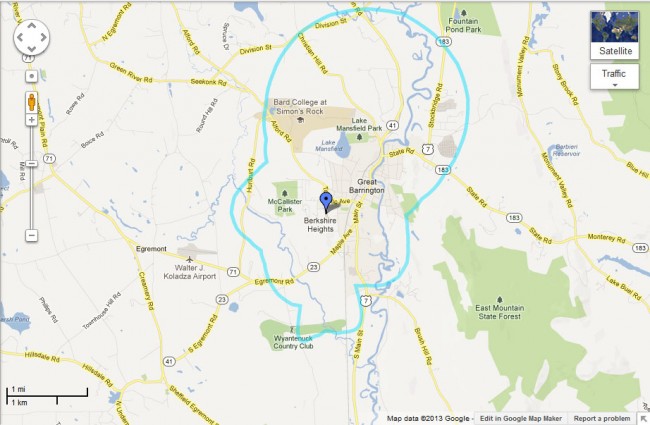

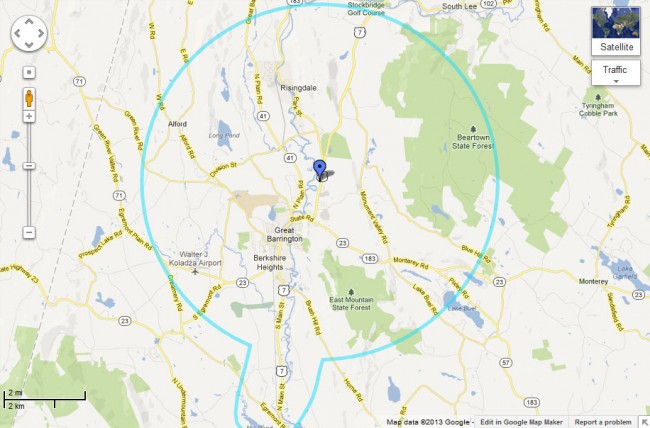

They have a translator on 94.1 MHz, W231AK. This is an example of when an FM translator on an AM station is a benefit to the community of license. W231AK has recently been moved from the top of the roof of the Fairview Hospital to the WSBS AM tower. During this move, the ERP was increased from 35 watts to 250 watts and the highly directional antenna was replaced in favor of a 2-bay half wave spaced circularly polarized Shively 6812.

Not only did the move increase the translator’s coverage area, it also reduced operating expenses for the radio station, as they no longer have to pay rent or TELCO charges.

The main transmitter for the AM station is a Harris SX2.5 . It transmits from a 79-degree tower, the tower and antenna field are well-maintained.

The studio has a new Audioarts Air4 console, which we just finished installing last December.

More pictures are available at NECRAT.

The station has an AC music format, which is quite popular. As the FM translator’s coverage has been quite limited until recently and there have been issues with the telephone company circuit taking the translator off the air, the majority of listeners are tuned to the AM signal. There is a live morning show and afternoon show, the rest of the day is voice tracked with music on hard drive. They have frequent contests and give aways. They also do local sports, community events, news and things like live election night coverage. In short, the station serves its community and, as demonstrated by a recent Chamber Business event at the station’s studio, the community appreciates its radio station.

There is nothing magic here; no gimmicks, IBOC, or another technical wizardry. This facility is at best, technically average, albeit well maintained. There is an older Orban Optimod processor, an older AM transmitter, and the original, electrically short tower. The station also has a working emergency generator. The only new tech is the web stream, which all radio stations should have.

The station is successful because of its programming, period. People love local radio. Making connections with listeners imparts a shared sense of community. Being on the air with a local presence during storms, even when the power is out, is a big deal. When it comes to relevance within the community and local businesses; in 2013 all radio stations need to earn that.

Conclusion:

I do not suffer from technophobia; when digital radio was first proposed, I welcomed the idea. It was not until I began looking at the technical proposals and iBiquity’s proprietary system that I became concerned. After hearing the initial implementation of AM HD radio on WOR in NYC, I was not impressed with either it’s audio quality or the side band interference that the analog/digital hybrid AM HD system created. What is of even greater concern is the propensity for government regulatory agencies to rubber stamp technical proposals by lobbying associations without testing or even fact checking.

Digital modulation methods at medium frequencies present a unique challenge where the ratio of the signal bandwidth to available frequency spectrum becomes too great to be practical. This is exacerbated at the lower end of the band where side band symmetry is difficult to achieve at ±15 KHz required by the all digital and the analog/digital hybrid version of AM HD radio.

Clearly, AM radio needs a technical revamping. Can it be saved? Yes. Is it worth saving? Yes. Is a yet unproven proprietary digital modulation scheme the way to do it? No.

And that is all I have to say on the matter.