Like any good government agency, the FCC in conjunction with FEMA is working on upgrading the acronym-heavy EAS system with CAP, which stands for Common Alert Protocol. CAP includes something that FEMA has been working on something called IPAWS, which stands for Integrated Public Alert Warning System.

The FCC is still in the comment/response process (FCC Docket 04-296) which can get long and drawn out. I would not expect to see any NPRM until late fall 2010 with any changes taking effect in early 2011 or so.

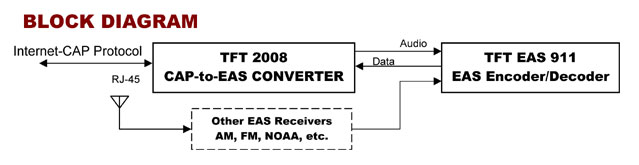

Basically, CAP looks like this:

An EAS to CAP converter monitors a CAP source (think e-mail server) and when a CAP message is received, it converts it to EAS protocol and sends it to an input source of an EAS encoder/decoder. The EAS encoder/decoder then passes that information through and broadcasts it. Of course, the EAS encoder/decoder can still be programmed to pass through specific types of messages for specific areas and ignore all others.

Thus far, several manufacturers have designed CAP converters for use with existing EAS units:

- TFT, Inc model 2008 CAP to EAS converter

- SAGE Alerting Systems ENDEC

- Gorman Redlich CAP to EAS decoder system

- Digital Alert Systems DASDEC-II

- Trilithic systems EAS plus

Implementation would look something like this:

For a TFT-2008 system. Others such as SAGE and Trilithic are integrated into the EAS encoder/decoder units. Basically, the CAP part of the EAS system needs an ethernet port with access to an IP gateway to receive messages from the CAP server located off site. That is the weak link in the system, as far as I am concerned.

It is not like some of our so-called trading partners have been trying to tinker with the inner tubes or anything. It is also not like that same trading partner makes most of the cheap ethernet switches and routers found in many radio stations, hardware that can be easily configured remotely. Configured to redirect certain IP addresses to new, exciting, and exotic locations such as Iran or Pakistan.

Perhaps I am paranoid, or not. It falls back to my time in the military when somebody said “It’s good to be a little paranoid if everyone is out to get you.”