How effective are they at filling in or expanding coverage for FM stations? The answer is, it depends. Most have heard of the quadcast around New York City on 107.1 MHz formed in 1996-98. It was well documented in Radio World and several other publications as a clever way to overcome the suburban rimshot problem. Four signals on 107.1 were synchronized using GPS timing data, then fed the same program material. They were WYNY, Briarcliff Manor, NY; WWXY, Hampton Bays (Long Island), NY; WWYZ, Long Branch, NJ; and WWYY Belvidere, NJ. These being four separate Class A FM stations, the 60 dBu contours did not overlap. There was some mutual interference in some areas, but there were few if any reception negative zones where the signal strength is equal between stations.

In early 2003, I was a part of the disassembly of the quadcast. In the end, it is difficult to point to any one thing that leads to the breakup. The station’s owners, Big City Radio, had filed for bankruptcy. I am not sure if the company ever had the correct formula for marketing and sales, given the strong suburban, but weak and lacking building penetration in Manhattan signal. The station initially had a country format, something that armchair quarterbacks said would not work in New York City. After a few years, Big City changed the format to Rumba, a Spanish/Caribbean music format, which did worse than Country. The fact is, that it never lived up to expectations and the station was worth more separately than together. Given the right circumstances, it could have worked.

The other synchronized FM broadcasts are those where boosters are employed. These are a good deal more difficult to configure because the booster signal is within the main station’s 60 dBu contour. Often cases, where there is severe terrain shadowing or other limitations, a well-positioned booster that is in a population center can greatly improve the signal in those areas. This was formerly the duty of an FM translator, however, those stations seem to be taking on a life of their own, without regard for the intent of the current FCC rules. Boosters can also be called a single frequency repeaters or single frequency network (SFN).

The disadvantages of an SFN are the aforementioned negative reception areas. To the receiver, this will create a multipath or picket fencing situation, which is objectionable to most listeners. The advantages are, of course, better coverage in key areas, spectrum efficiency, and the ability to create a network of common frequency systems. Think of how easy it would be if all NPR stations were all on the same frequency, for example.

The key to making a booster work is to synchronize several aspects of the RF and Audio signals:

- RF carrier frequency

- Stereo pilot frequency and phase

- Audio amplitude and phase

The RF carrier frequency, stereo pilot frequency, and phase are locked with a GPS. Most transmitters have a 10 MHz or 1 PPS input for this.

The audio amplitude and phase synchronization are slightly more complicated. Basically, all of the audio should be coming from one audio processor and the path to the individual transmitter sites has to be very low latency. RF STLs work for this setup well, if there are suitable paths.

Once that is established, the audio timing is used to move the interference zone away from undesirable areas. There will always be an interference zone where both signals are received at the same relative strength causing dropouts.

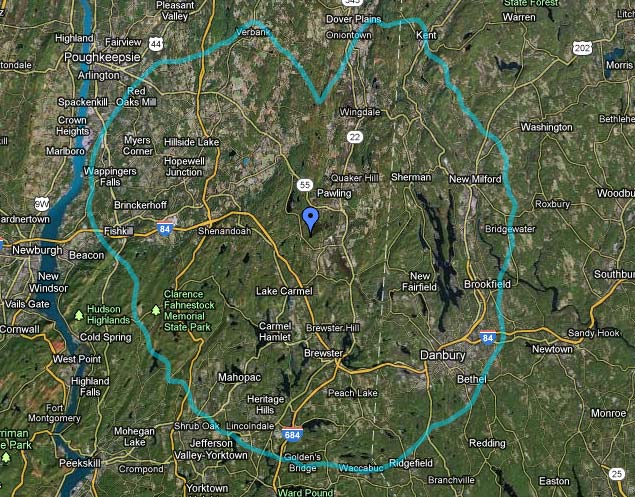

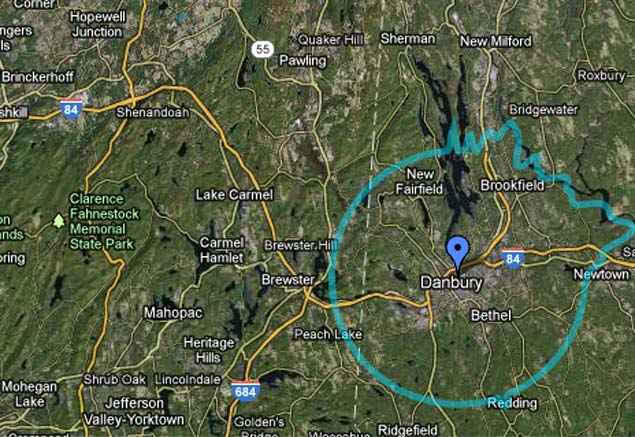

This is the situation with WDBY in Patterson, NY. The main transmitter site is located on a hill in Patterson and has a power level of 900 Watts at 610 feet (186 meters) HAAT. The main population area is Danbury, CT, to the southeast, about 12 miles away. Between the two, there are several imposing hills, which create reception issues in Danbury. Therefore, WDBY FM1 was placed in service at the Danbury Medical Center. The booster has a power output of 1,200 Watts, at 0 feet (0 meters) HAAT (49 meters AGL).

Therefore, the southern area of the 60 dBu contour is filled in by the booster. The interference zone between the two transmitters is determined by the amount of delay in the audio between the two units. If both are time the same, the interference will occur at precisely 1/2 the distance between the transmitter sites, which in this case is 10.18 KM from the booster. Looking at the population maps, it might be better to move that more toward the north, away from Danbury.

The formula for computing audio delay time is:

A-B=C where A is the distance between the transmitters and B is the distance to the interference zone from any given transmitter. The product of that is multiplied by a constant of 3.34 to obtain the time delay in microseconds. Therefore, if the interference zone is desired to be further outside of Danbury, say 15 KM away, then the equation looks like this:

20.358 kM -15.0 kM = 5.358 KM

5.358 KM x 3.34 = 17.89 μS delay from the main transmitter site will put the interference zone out in the middle of nowhere, away from Danbury. This is the total delay between the two stations, therefore any difference in STL paths needs to be included in this figure.

Nautel has a good webinar on SFNs which can be found on their website: Single Frequency Networks Webinar

Nautel equipment has most of these features built into it, therefore, the implementation of an SFN using Nautel exciters and transmitters should be relatively straightforward.