That question was posed to me this afternoon by a coworker. It is, indeed, a good question. Certainly, broadcast engineering is more of a vocation than a career, especially where it concerns radio stations. Why would anyone work for low wages, long hours, little or no recognition, 24/7 on-call, and or unappreciative management?

Further, in this risk-averse, zero-defect, micromanaged environment, what is the upside to being a radio, RF, or broadcast engineer?

I suppose one would have to have some appreciation for history. One of the reasons I cover radio history here or certain historical events is that without knowing the roots of radio, one would be hard-pressed to find today’s version of radio broadcasting even remotely interesting. Understanding that before there was the internet, web streaming, Spotify, Youtube, Sirius/XM, television, cellular telephones, 3G, 4G, and so on, radio was mass media. Radio was people-driven, and people-oriented, not an automated computer programmed from afar. People tuned in for the music but also the personality and the personal connection.

Growing up in the late sixties and seventies, radio was my link to the outside world. As a young boy living in rural upstate New York, my mostly agricultural surroundings seemed a bit provincial. Through radio, I was able to listen to the clear channel stations from New York City, Chicago, Detroit, Nashville, Charlotte, Pittsburgh, Washington DC, Cincinnati, etc. The street that I grew up on did not get cable TV until 1980, prior to that, the rooftop antenna received exactly two channels when it wasn’t blown over by a storm. The black and white TV was often broken, sometimes for over a year. It was of no great consequence, however, when nightly under my pillow, the battery-powered transistor radio was employed until midnight or later.

When I got older, shortwave radio kits were built and listened to.

Through that medium, I learned about life outside of my small town.

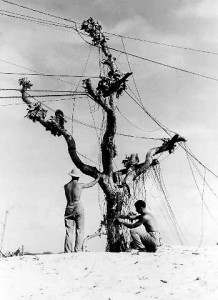

The upside is being a part of something that can still be great, although those stations are getting harder and harder to find. Still, there is a certain pride to a job well done, a clean transmitter room, and a well-tuned machine working into a properly tuned antenna. Does anyone even appreciate that anymore? I do. Lou Dickey, John Dickey, Bob Pittman, Leslie Moonves, and other CEOs may not care that the transmitter site is clean and well-kept. They may, in fact, question it as a waste of salary. I appreciate it. Fellow engineers will appreciate it, too.

Starting a transmitter, especially a high-powered tube transmitter, is a joy all its own. Nothing against Nautel, they make fine transmitters, however, when pressing the on button, the outcome is almost assured: The transmitter will turn on. Not so with certain tube-type transmitters. Pressing the plate-on button for one of those can have many different outcomes. There is a certain thrill when it all works right, the first time. There is a certain pride in driving away from a transmitter site, listening to the radio, and knowing; I caused that to happen.