Aside from it hasn’t worked… Over the last several, the FCC has released no fewer than five proceedings regarding EAS. To date, few, if any meaningful changes have taken effect. The stated purpose of the Emergency Alert System (EAS) is to:

- provide the communications capability to the President to address the American public during a national emergency.

- may be used by state and local authorities to deliver important emergency information, such as AMBER alerts and weather information targeted to specific areas.

Seems pretty straightforward. Local weather emergencies would seem to be the most likely reason for EAS activation, followed by things like Amber Alerts, chemical spills, evacuations, etc. To meet those ends, the FCC mandates that radio (traditional and IBOC), television, cable, wireless cable, direct satellite TV, and satellite radio participate in some way or another. So far, it seems like a fair idea. Then comes the implementation, which is flawed. To start with, EAS still relies on a daisy chain relay system designed during the 1960s for CONELRAD. The over-the-air monitor assignments of other broadcast stations are the only mandatory information sources in the system. Other, more relative local sources such as the national weather service, local government, and so forth are optional. Next, the most used and most useful part of the EAS, local and state-level alerts are completely optional. Very little or no information is provided to local government agencies on how to access EAS in the event of an emergency. Then the issue becomes one of unmanned stations. The initial EAS message goes out over the airwaves, which takes about 2 minutes at most, then it’s back to the music. No amplifying information, check back for more information when it becomes available, etc. Nothing. It has occurred in several cases where a radio show is voice tracked, complete with a weather forecast, which is the opposite of real-time weather warnings. If one happens to miss the initial EAS broadcast because they were listening to another station or whatever, well, too bad. Finally, the National Weather Service itself over-activates. One line of summertime thunderstorms passing through the area can trigger 10 or even 20 EAS alerts. Over-activating, with the same digital tones (rrrrrrannk, rrrrrrank, rrrrrank) followed by the EBS tone than some computer-generated voice just gets annoying. To summarize:

- The national EAS has never been tested, who knows if it will work

- The EAS relies on unreliable over-the-air daisy chain relays for its mandatory monitor assignments

- Local and State level EAS (including weather-related alerts, something that could be really useful) is optional

- When connected to the NOAA weather radio system, the NWS overuses the EAS activations

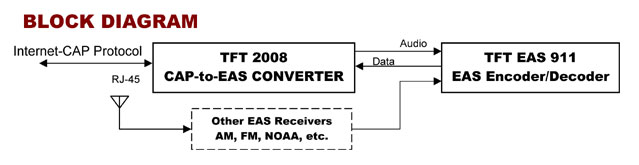

Here is an idea: For at least ten years now, the idea of a CAP has been batted around. It seems like a good idea, let’s do that. Get rid of EAS, send emergency information to everyone’s cellphones or whatever, and stop fining broadcasters for missing a monthly test. The weak link in the EAS is the broadcaster’s themselves. History has shown (over and over again) that the current crop of radio station owners cannot be bothered to meet even the simplest of their public obligations. The FCC has shown it is only interested in collecting big fines for missed EAS tests, not actually making the system work. The system is broken. As terrestrial radio (and TV) goes terminal, the public will still need to receive emergency information, the CAP idea can fill this requirement. It is time to pull the plug on EAS once and for all.