Amplitude Modulation (AKA AM) was the first modulation type to impress audio on an RF carrier. Prior to this, information was transmitted via on/off keying of a continuous wave transmitter using Morse code or some equivalent.

There are several methods for generating AM in a transmitter.

1. Low-level modulation. The modulation is developed in the first stage RF section, then amplified by subsequent stages to full power. Simple and easy to implement, especially for mobile transmitters and SSB installations. Disadvantages come from the need for linear amplification through all the stages requiring class A or AB amplifiers and do not reproduce wide band AM well.

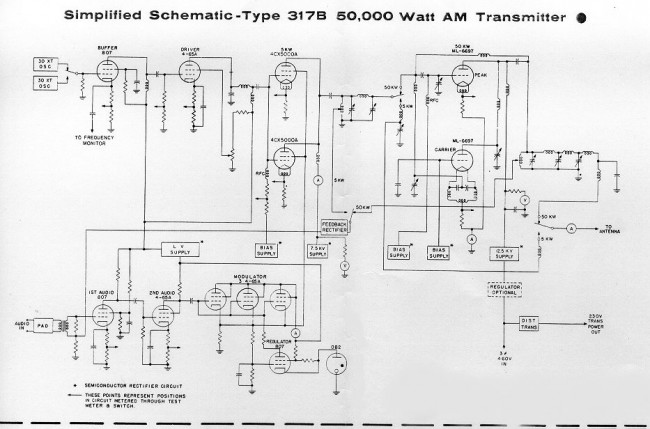

2. Doherty modulation. William Doherty came up with an ingenious way to use a low-level linear modulator with good to excellent efficiency. Under full carrier, no modulation conditions, the carrier tube is generating the RF carrier, and the peak tube is mostly cut off (very little current). When modulation is applied, the peak tube then begins to conduct, the output of this tube is combined with the output of the carrier tube through a 90° LC network, which is the same as a 1/4 wavelength transmission line. The effect of this is to lower the output impedance, thus allowing the carrier tube to modulate 100 percent.

Later, Continental Electronics and Jim Weldon somewhat modified this system in their 317C series high-power transmitters.

3. High level or plate modulation. The RF and Audio sections are developed separately within the transmitter, then combined in the final stage of the transmitter. Older systems used a modulation transformer. The advantages are all the amplifiers can be run class C or greater, which reduced electrical consumption and power supply requirements. Much higher power levels are achievable with this design. These transmitters also reproduce wide-band audio much better than low-level modulated units. They are also extremely rugged. Disadvantages are the system requires large audio sections and they take up a greater area and are not as efficient as later modulation methods.

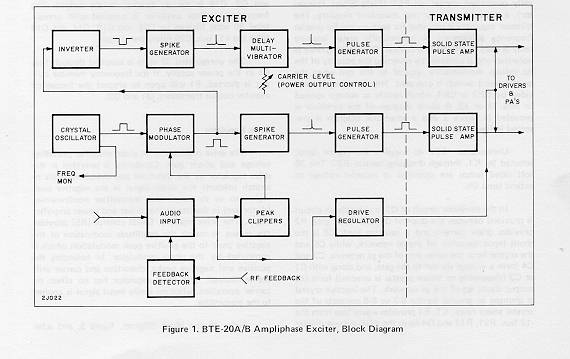

4. Ampliphase. A phase-modulated system developed by RCA where the transmitter developed two RF signals in the final, 135 degrees apart. To modulate the signal, the phase relationship between the carriers is varied, more toward 180 degrees would be a negative peak, and more toward 90 degrees a positive peak. These transmitters required less space and were more efficient than traditional plate-modulated transmitters. They required careful setup and tune-up to reduce distortion and somewhat unfairly earned the name “amplifuzz” from some engineers.

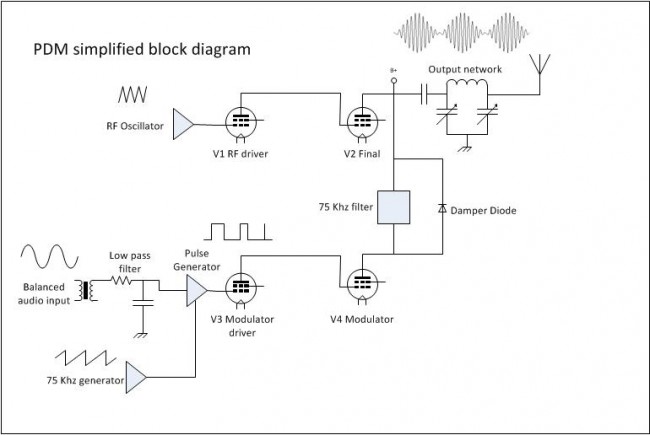

5. PDM or PWM. This is also a high-level modulation scheme but with some slight variations. The carrier power level and modulation levels are set by a PDM encoder card. In Harris transmitters, the PDM frequency was 75 KHz. The carrier is set by the amplitude of the PDM waveform, and the modulation is determined by the duration of the pulse. PDM transmitters require power supply voltages about twice the voltage of a standard high-level plate-modulated transmitter. They also require a damper diode to conduct the B+ voltage to back to the power supply during negative peaks, otherwise, the PA voltage will attempt to rise to infinity. I have found the damper diode to be the weak link in a tube-type PDM transmitter.

Solid state transmitters also use this design with either MOSFETs or BJT, which are then combined in parallel to generate the required output power. This is most often called “Class E” or something similar. In that system, each pair of modulator MOSFETs has its own fast-acting damper diode, usually protected by a fuse.

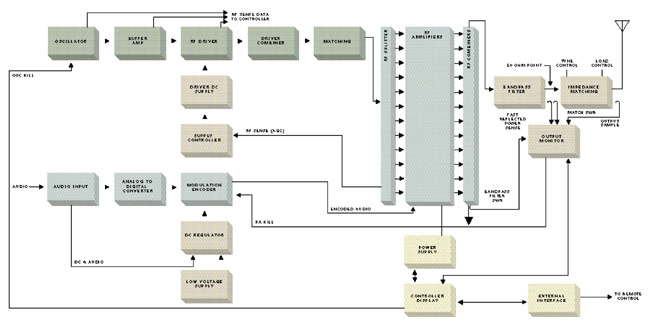

6. Direct Digital Synthesis. This is a patented design from Harris Broadcast used in their DX series transmitters. The incoming audio is sampled at either the carrier frequency or 1/2 the carrier frequency depending on where in the band the station falls. The solid-state PA modules are then switched on and off at the carrier frequency with the audio levels imposed on the carrier information. The explanation is simple, the application is complex:

Of all these transmitters, the Harris DX series is the most efficient from a power input (AC) to power output (RF) perspective. There are several methods of reducing electrical use by reducing carrier power levels during lulls in modulation. The Continental 418E and later series transmitters can reduce carriers up to 6 dB using CCM. Harris and Nautel use similar systems on their DX and XL transmitters respectively. The wheatstone corporate blog has an article: Greener AM transmission Methods that details others.

As far as simplicity, serviceability, and rugged design, the high-level plate modulated transmitters cannot be beaten. Many Amateur Radio operators build these units from scratch using old parts, tubes, and other reused equipment readily available, often for free. I have, in fact, donated several 1 KW AM transmitters to ham radio operators over the years.

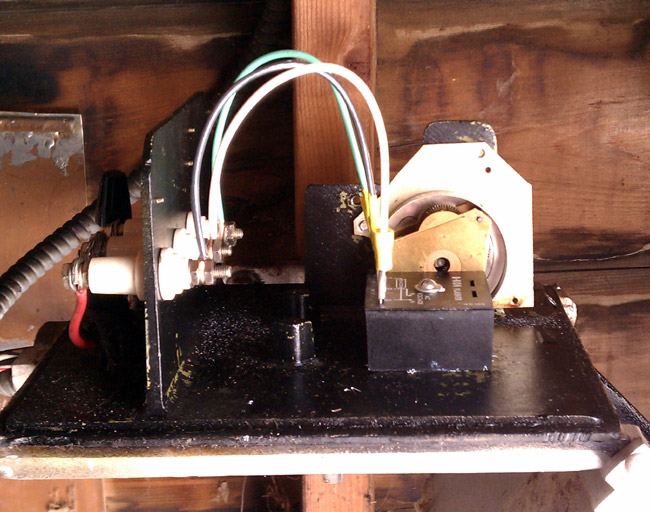

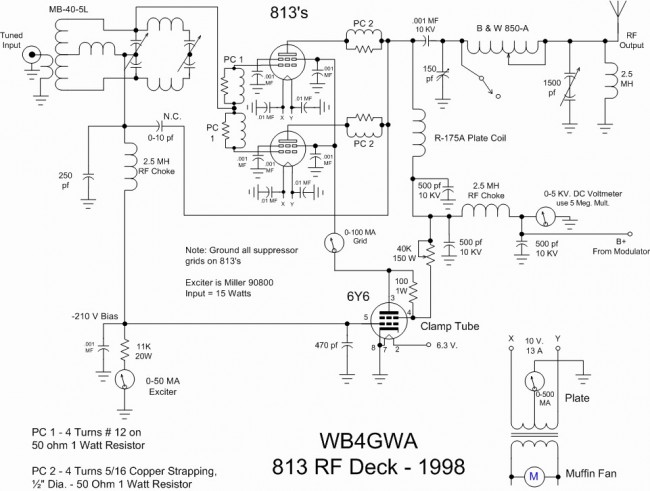

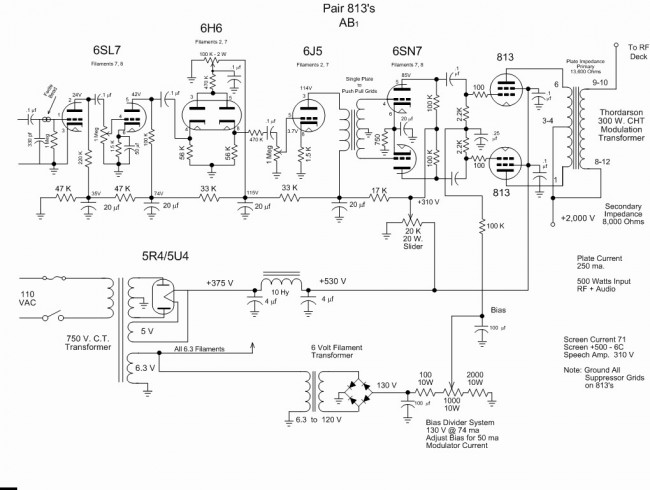

If I were to design a “transmitter of last resort,” to use in case everything else fails, it would look something like this:

The disadvantage of that design is it requires a 2KV power supply, which has its own set of safety concerns. I might substitute 833s for 813s and use heavier iron in the modulation transformer. That way the transmitter could develop a 500 to 1,000-watt carrier. The great thing about tube transmitters is, given the right output components, they can be tuned into almost any load. They are also easily adaptable for emergency operation into temporary antennas.