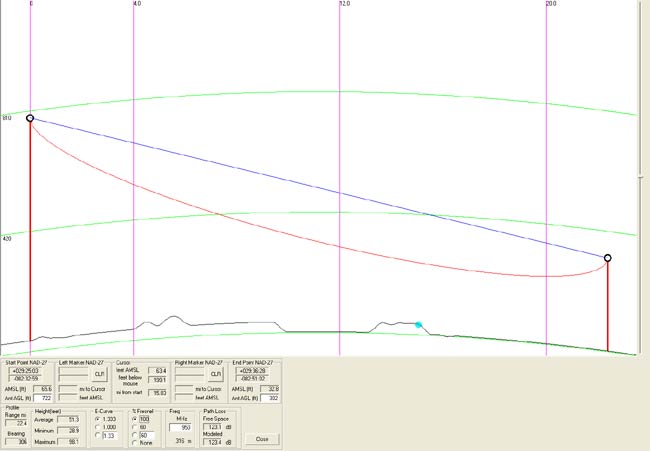

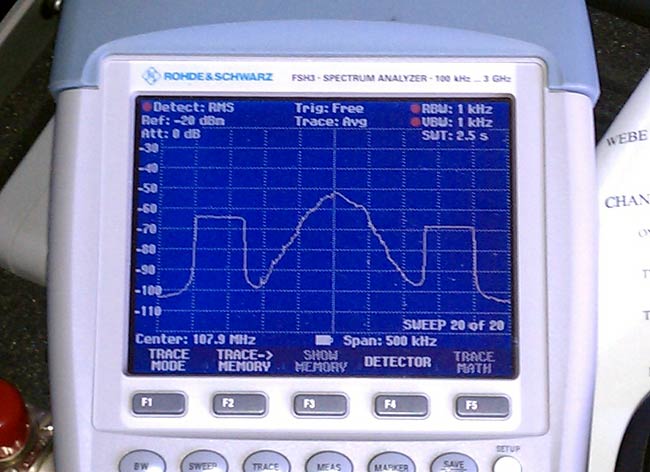

The standard FM channel in the United States, as defined by the FCC is 200 KHz (See CFR 47 73.201). The occupied bandwidth of an FM IBOC signal, as created by Ibiquity, Inc., is 400 KHz. See the below picture:

A picture is worth a thousand words. Engineering types will understand this without explanation. For non-engineering types, here are your thousand words (or so):

On the left-hand side of the screen is the signal strength scale. Each vertical division is 10 dB. This is not absolute signal strength, it is referenced to -20 dBm. However, it gives a good relative signal strength for both the analog carrier and the IBOC carriers. The analog carrier is centered on the screen, it slopes upward like a steep mountain, peaking at -50 dBm relative. The IBOC carriers are on either side of the analog carrier, they are flat, approximately 75 KHz wide, and peak approximately 20 dBm below the analog carrier (-20 dBc). For some reason, likely the bandwidth and/or impedance match between the antenna, high-level combiner and the two transmitters, the left IBOC carrier is actually peaking around -14 dBc.

The span, as noted on the bottom right-hand side of the screen is 500 kHz. Each horizontal division is 50 KHz. The entire span of the measurable signal is eight horizontal divisions, thus 400 KHz.

As noted above, the allocated channel bandwidth is 200 KHz, thus this station is exceeding it’s allocated bandwidth by 100%. This is allowed under CFR 73.404, which is titled “Interim hybrid IBOC DAB operation.”

IBOC proponents will make the argument that FM radios work on something called “The capture effect,” which is to say that if two signals are on or close to the same frequency, only the stronger signal will be demodulated. Thus, the IBOC carriers have no effect on the adjacent channels that they are interfering with so long as the adjacent signal is stronger than the IBOC carrier. The argument is further carried forward by assuming that with a station’s protected contour (60 dBu in most cases), the IBOC carrier will never exceed that analog carrier.

That is not necessarily true, especially in areas where terrain (and buildings, underpasses, unintentional directionality in transmitting antenna, etc) can attenuate signals close in causing the IBOC signal to become equal to or stronger than the adjacent analog signal. This effect causes picket fencing. Lower powered FM stations; class A, LPFM, etc, are especially vulnerable to this effect.

Further, even in areas where the analog carrier is stronger than the IBOC carrier, the noise floor has been moved from -100 dBm or so to -70 dBm, which is a 1,000 times greater. To assume that raising the noise floor by 1,000 times will have no effect is, as they used to say in the Navy, making an ASS out of U and ME. Mostly you, in this case. This affects the receiver by making it less sensitive, it will also add noise to the demodulated signal as the elevated noise floor will show up as background hiss. Even further still, higher IBOC carrier levels, as authorized by the FCC in January of 2010 can interfere with the station’s own analog carrier.

According to both Ibiquity and the FCC, which stated in the Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, the reason for interim IBOC operations are:

iBiquity’s IBOC DAB technology provides for enhanced sound fidelity, improved reception, and new data services. IBOC is a method of transmitting near-CD quality audio signals to radio receivers along with new data services such as station, song and artist identification, stock and news information, as well as local traffic and weather bulletins. This technology allows broadcasters to use their current radio spectrum to transmit AM and FM analog signals simultaneously with new higher quality digital signals. These digital signals eliminate the static, hiss, pops, and fades associated with the current analog radio system. IBOC was designed to bring the benefits of digital audio broadcasting to analog radio while preventing interference to the host analog station and stations on the same channel and adjacent channels. IBOC technology makes use of the existing AM and FM bands (In-Band) by adding digital carriers to a radio station‘s analog signal, allowing broadcasters to transmit digitally on their existing channel assignments (On-Channel) iBiquity IBOC technology will also allow for radios to be ”backward and forward” compatible, allowing them to receive traditional analog broadcasts from stations that have yet to convert and digital broadcasts from stations that have converted. Current analog radios will continue to receive the analog portions of the broadcast.

Few if any of those goals have been met. As far as the forward/backward compatible thing, it just isn’t so unless a person actually owns an HD Radio. As noted in previous posts, few consumers have seen fit to purchase an HD Radio, nor have car manufacturers taken to installing them en mass in new cars, so there is no forward compatibility. Instead, we have FM radio stations interfere with each other and themselves in an attempt to “modernize” the audio broadcasting business. This is a bigger problem for small, community radio stations that can neither afford to install the expensive, proprietary HD Radio system nor broadcast quality receivable signals with an adjacent HD Radio signal raising the noise floor by 1,000 times or more.

I can think of no other greater threat to free over-the-air broadcasting than HD Radio and the degradation of AM and FM services that come with it. The consumer has shown that they don’t care. If given the choice between free over-the-air broadcasting that has mediocre programming and is full of interference, and some type of paid internet streaming service that sounds reasonable with good programming, they’ll go for the latter.

In short, some cobbed-together digital modulation scheme is the last thing that radio needs right now.