We all remember the first radio station we worked at or visited. Mine was a military communications station that also worked as a maritime coastal station. I was putting my past experiences down on paper when I started on my experiences there and thought it might make some interesting reading. I did two parts, the first was based on my personal experiences, and the second has to do with the history of Coast Guard Radio Guam.

So this is part I:

I arrived at NRV in May of 1988. At the time, I didn’t know that I was witnessing the end of an era. Had I known, I would have made some copies of my 500 KHz (500 KHz was the Morse Code (AKA CW) distress and calling frequency) logs and other things of general interest.

Upon arrival, I could copy code at 20-25 WPM and thought I’d have no problems sliding right into the routine. The 500 KHz position (position 1) was a good place to become acquainted with commercial CW operations, as opposed to the procedures we learned in Radioman A school. Position 1 was a headphone watch and the frequency was monitored 24/7, without exception. In the tropics, MF (Medium Frequency) does not carry far at all during the daytime; so most of the logs during daylight hours had “NO SIGS” typed reliably every 5 minutes. Unless a ship was within a couple of hundred miles of Guam and specifically calling NRV, the only thing heard was the weather and Notice to Mariner’s announcements we sent out ourselves.

Nighttime was a different story. Often times it was difficult to keep up with all the Chinese Coastal stations chattering back and forth. XSG (Shanghai) seemed to be the net control station, telling others XSE, XSO, XSO4, XST, etc to go up for traffic. I imagined some poor guy sweating it out over a straight key in a tin roof shack. Years later I saw pictures of XSG in the late 80’s early 90s and they put our old worn-out equipment to shame.

At night on 500 KHz, all sorts of stations could be heard, 9VG, 9MG, P2R, P2M, VPS with their top-of-the-hour time tick, JCS, JNA, JNB, HLO, HMC, VIT, VIB, NPO, NMO and occasionally KFS and KPH. Copying all those signals through static bursts and interference was good practice. JNA and JNB were the Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Force stations. They sent out the TTT (TTT is a marine safety message) and XXX (is an urgent message) messages for the Japanese waters if there were any. XXX was usually related to man overboard or some other life-threatening matter. We would TTT a typhoon warning if it was in our SAR area. A lot of times, nighttime on 500 KHz was like catching up on gossip. I would often go off to listen to the XXX or TTT messages (keeping one ear on 500, of course) just to find out what was going on. In addition to monitoring 500 KHz, this operator also manned the three SITOR teletypes. They were on 8/12/16 MHz nighttime and 12/16/22 MHz daytime. Most often, SITOR was used by merchant ships to send in AMVERs or OBS. There were also several USNS ships that would come up and ask for press, which we were happy to send them. Weather and Hydropac broadcasts were also keyed from the old Model 28 teletype sets using torn tape relay. The operator in position four would edit all of the weather messages, removing the military header and paging information, then string them all together onto one tape and bring it over. During Typhoon season, position four could get interesting. We used the model 28s until 1989 when they finally installed Unisys C-TOS terminals.

Position 1 was a full-time watch, if you needed to go to the bathroom, the watch supervisor would come in and sign onto the log.

Position 2 seemed to be either really busy or really boring. The position 2 operator usually was responsible for general clean up of the COMMSTA after mid-watch, emptying the garbage, shredding old messages and logs, etc. If there was a cutter underway, it could get interesting and the air guard was always busy. Other than that, sending and receiving routine and priority messages from Iwo Jima and Marcus LORAN was about it. On the overnights, pretty much nothing went on except once we had to send out a flash tsunami warning to the LORAN stations at 2 am. Fortunately, nothing happened, but I often wondered what they would do if a tsunami did strike those islands.

Position 3 was either great fun or greatly intimidating. This was the HF CW position and NRV prided itself in its CW operators. I remember breaking into that position and getting used to the commercial CW procedures. It was somewhat of a free for all, especially around the 00 OBS/AMVER sked. In the beginning, I easily mastered the AMVER format; get the ship name and call sign right, then it was mostly numbers and slant bars after that. OBS were all numbers; a BATHY was just a long OBS that began with JJXX. For some reason, CW numbers were easy for me. COMLE’s, MEDICOS, and fisheries messages, on the other hand, gave me fits until I became more proficient.

I remember one particular ship, the Golden Craig/3EOK3. He was an inter-island tanker sailing between Guam, Yap, Saipan, Majuro, Ulithi, Truck, Palau, etc delivering gas and distillates. He’d come up every other day and send a report back to the home office, Mobil Guam, with what he delivered and where. The older, more experienced operators were always there to lend a hand if there were a MEDICO or other similar situations. Towards the end of my stay on Guam, I was copying easily 35 WPM and got my speed key certificate.

The way the position was set up, there were six receivers tuned to the HF calling channels 4/5 for 8/12/16 MHz at night and 12/16/22 MHz during the day. At night, we also monitored the HF lifeboat frequency 8364 KHz. When a ship called “NRV NRV NRV NRV NRV…” on one of the calling channels, the procedure was to mute the receivers until the calling frequency was isolated, then stop the call tape send “DE” and take down his call sign and working frequency. After I became proficient, I wouldn’t mute the receivers at all, I’d just stop the call tape. The ship wouldn’t wait for the DE, he’d just send his working information, usually something like “NRV DE EREI OBS UP 680 K” I knew that the 12 MHz working frequencies were in the 680 range, so I’d just send “UP” and tune my working receiver to 12680 and send EREI DE NRV K at which point he’d come up and send his OBS. EREI was the R/V Ocean, a Soviet research vessel and there were several Ops aboard. The one that I could recognize by his fist was Oleg, who was a good CW operator. All the Russians were good CW operators. I had a few “off the record” conversations with Oleg.

During the 00Z (UTC, 10 am local time) OBS/AMVER sked, I’d often stack traffic up, acknowledging each call sign and assigning a QRY (turn) number. After I got to about 6-8 vessels waiting, I’d work through my list and start over again. That was much fun indeed, but it lead to some very brisk exchanges.

Speaking of the lifeboat frequency, one night on the mid watch, I was sitting around listening to the crickets chirping when I heard SOS SOS SOS SOS SOS SOS sent at about 10 words per minute. I nearly jumped out of my skin; I stopped the call tape and sent “VESSEL SENDING SOS DE NRV QRA? QTH? K. This time I quickly switched off all the receivers and discovered it was on 8364 KHz. The slow SOS continued so we called over to the “Elephant Cage” the AN-FRD 10 Wullenweber DF antenna next door. They quickly came up and got a fix on it off the east coast of Australia. We called the Canberra RCC and they said they were on it. Canberra had a program like AMVER called AUSREP, from which they could find a ship nearby. I imagined some poor guy in a leaky lifeboat cranking the handle on the emergency lifeboat radio, not knowing if it was being heard or even working. We found out the next day, I wasn’t far off. A freighter was diverted and picked up 20 survivors from a cargo vessel that sank. Even in 1990, Morse code was still saving lives.

We were a busy little COMMSTA most of the time. In addition to the odd distress, we also received quite a few MEDICO messages. Some of these were from ships far, far away from any medical assistance and often the radio officer did not speak English. Some of these MEDICO messages were relayed to CIRM ROMA, the internationally recognized medical advice agency, or they would be handled locally by the Naval Hospital. They would range from an illness to trauma.

I think the best one was a British-flagged vessel whose chief engineer fell down a hatchway and broke his leg. They happened to be in the vicinity of the USS Carl Vinson strike group operating off the coast of Japan. Within about 3 hours of them contacting us, the Vinson had sent a helicopter over and evacuated the casualty to Okinawa. I think the Brits were impressed, but it is often hard to tell with them. For us, it was business as usual. By the end of my tour, position 3 had become my favorite.

I also had my favorite ships/operators to work with. SEALAND NAVIGATOR/WPGK, PRESIDENT WASHINGTON/WHRN, LNG LEO (can’t remember the call sign), and so on. Some of those ships called on Guam, and we would always try to get down to the port and visit with the REO.

Position four was known as the broadcast position. From here HF CW broadcasts that covered the Western Pacific and Indian oceans were keyed. We sent out weather and hydropacs. We also broadcast weather on HF voice. During typhoon season, these broadcasts became long and it was often a rush to get all the tape editing and splicing done for the SITOR broadcast, which followed. The HF voice broadcasts were on the SCN network frequency, 13 MHz day, 6 MHz night. We ended all of those broadcasts with the following statement:

COMMENTS CONCERNING THESE BROADCASTS ARE REQUESTED. YOU CAN SEND YOUR COMMENTS TO, COMMANDING OFFICER, COAST GUARD COMMUNICATION STATION GUAM, POST OFFICE BOX 149, NOVERMBER CHARLIE WHISKY PAPA, FPO SAN FRANSICO, CALIFORNIA 96630

THIS IS UNITED STATES COAST GUARD GUAM COMMUNICATION STATION, NOVEMBER ROMEO VICTOR, OUT.

There was also some guy in the Philippines that would come up after a typhoon warning and say “THANK YOU NRV” or “THANK YOU GUAM COAST GUARD” particularly on 13 MHz.

This position also guarded 2182 KHz. Much like 500 KHz, during the daytime, there was not a lot going on. At nighttime, there were all sorts of signals, including drift net buoys and Chinese fishermen having long animated conversations. Also heard on 2182 at night was Singapore Radio/9VG, which always seemed to have female operators, who, quite frankly sounded like some sort of radio sirens coming through the speaker. I imagined they were quite beautiful, theater of the mind as it were.

It was in position four that I worked my first distress on 2182, the M/V Windjammer Pacific, a converted WWII minesweeper turned into a touring boat. They lost their way on the fringe of a typhoon somewhere near Yap. The engine conked out and they were shipping water in the engine room. It took a couple of days to find them since even they didn’t know where they were. In the end, a C-130 from Barber’s Point found them and dropped pumps, food, and fresh water. They were able to pump out the engine room and get restarted. The USCGC Assateague, which had recently replaced the Cape George, was sent out to meet them and guide them back to Guam.

There were many such incidents in the two and a half years I was there. Lost fishing vessels, overdue sailboats, man overboard, medical advice, and or evacuations, I can’t think of the number of lives affected, people we helped, the information we passed on, and lives we saved.

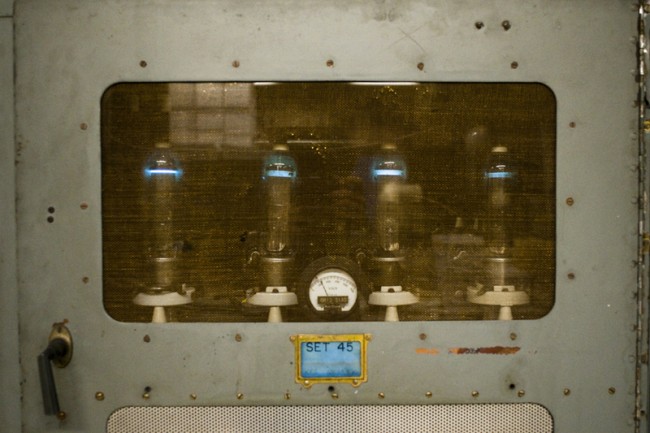

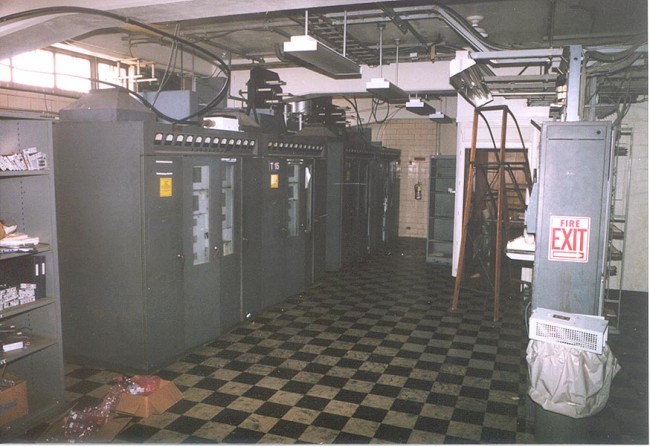

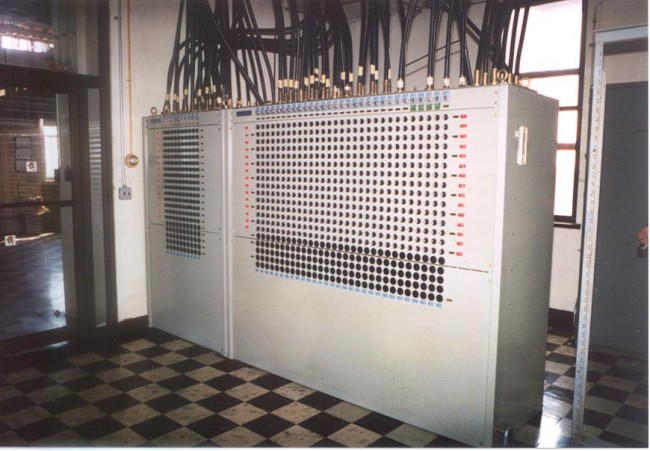

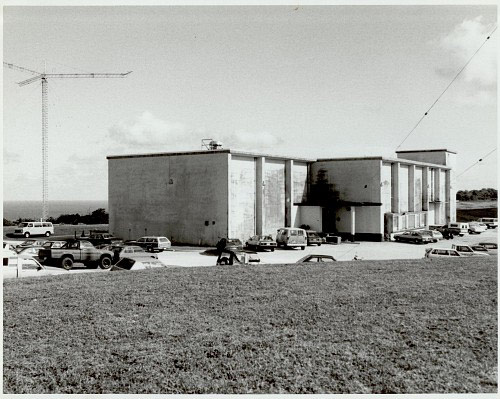

The facilities at NRV belonged to the Navy. Navy technicians came and fixed the teletypes when they broke, all of the circuits to the transmitter site ran on Navy cables through building 112 (AKA tech control) out to NRTF Barrigada, where Navy transmitters (FRT-70s) would transmit our information. As such, there was sort of a love/hate relationship with the Navy. The COMMSTA was located in Building 150 at Finegayan receiver site, which was built in the late ’50s. Most of the Navy functions had been moved to building 112, except the HF receivers, which were downstairs. There was one guy on watch; all he did was change the frequency on whichever circuit he was told to. The cable between building 150 and 112 was old and often failed. I spent hours of my life troubleshooting the XH1G circuit (and others) with TCF. I know that the Navy guys did the best they could with what they had. We were given tours of Building 112 and NRTF, after which I was glad I worked where I did.

Our receive antennas were an array of loops to the north of the building and several inverted cones, which replaced the rhombic rosettes that surrounded building 150. The 500 KHz antenna was a 1000-foot-long wire.

After I made 2nd class, I qualified as watch supervisor. Depending on who the CWO (Chief Watch Officer) was, I sometimes worked the supervisor’s position. It was mostly sending messages via landline teletype to the various Coast Guard commands on Guam, Okinawa, and Japan.

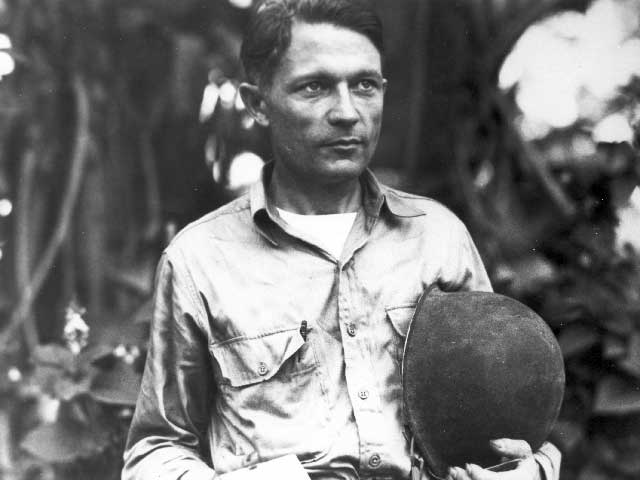

When the Coast Guard installed the Unisys terminals in late 1989, things improved. The building itself was interesting. Down the hall from the head (bathroom) was a stairway that led up to the roof or down to the basement. On the midwatch, roundabout 4:30 am local time, I’d often volunteer to bring the shredder chaff down to the dumpster behind the building. Oftentimes, I’d take a little detour up to the roof and look out at the Philippine Sea or across the antenna field at the wullenweber antenna. Very close to building 150 was something known as Tweed’s Cave. This was where George R. Tweed, RM1 USN hid out from the Japanese for 32 months during WWII. We hiked up to it several times, finding parts of corrugated steel and other artifacts, which, according to his book, Robinson Crusoe, USN, was used for roofing. It wasn’t much of a cave, more like a large crevasse at the top of a nearly 300-foot cliff. After going there two or three times, I completely understand how the Japanese never found him. Also, to the north and west of building 150 near the antenna field was an old Japanese antiaircraft emplacement.

We were cautioned about wandering around in the “boonies” too much, mostly due to the risk of unexploded ordinance left over from WWII. It seems there were quite a few bombs and artillery shells that would turn up on a somewhat regular basis. In one incident, elementary school children were found to be playing with a live hand grenade they found on the playground.

Towards the end of my tour, more and more folks from Coast Guard Electronics and Engineering Center, Wildwood, NJ began showing up. They were trying out the new Harris R-2368 receivers. They were doing things like hooking them up to phone lines and remote controlling them from PACAREA, Alameda, CA. The writing was on the wall.

I left Guam in May of 1991. In late 1992, I was living in Schenectady, NY, and happened to tune across NRV’s SITOR broadcast on 12 MHz. It was from the statement at the end of that broadcast; I learned that NRV would be closing down in a few days. By closing down, they were remoting the operation to COMMSTA Honolulu/NMO, but it was the end of an era. Guam was a great duty station and I feel honored to have been a part of NRV while it was still a functioning, live entity.

End of Part I.