As broadcasters, we don’t really hear that much about ceramic power vacuum tubes these days, as more and more broadcast transmitters migrate to solid-state devices. Once upon a time, however, power tubes were the engine that drove the entire operation. Tubes had to be budgeted for, stocked, rotated, and replaced on a regular schedule. Some of those dern things were expensive too.

Take the 4CX35,000A which was used in the Harris MW50 transmitters. The transmitter used two of these tubes, one in the RF section and one in the modulator. As I recall, new tubes cost somewhere north of $8,000.00 each from EIMAC. Plus, in the A models, there were two 4CX1500A driver tubes. All of which could add up to an expensive maintenance cost every two years or so.

The next best option was to buy rebuilt tubes. Rebuilt tubes were about half the cost of brand-new ones. Some people complain that rebuilds don’t last as long, or only last half as long as the new tubes. I never found that to be the case. I often found other factors that affected tube life far greater, such as filament voltage management, cooling, and by extension, cleanliness.

I can say I never had a warranty issue with ECONCO tubes. I cannot say that about EIMAC, as during the late 90s and early ’00s (or whatever you call that decade), I had several brand new 4CX3500 tubes that were bad right out of the box. These days, ECONCO and EIMAC are both owned by CPI.

I spoke with John Canevari from ECONCO who had a lot of information. For example, as the tube ages, the filament gets more flexible, not less. Most ceramic power tubes use a carbonized tungsten filament containing some small amount of thorium. As the tube ages, the filament can no longer boil off enough electrons and the emission begins to drop off. That is the normal end of life for a power tube. Occasionally, some catastrophic failure will occur.

There are many steps in the rebuilding process:

- Dud is received from the field, the serial number is recorded and the tube is tested in.

- The tube is prepped by sand-blasting the sealing rings

- It is opened

- The filament is replaced. In 60-70% of the cases, the grid is replaced. In those tubes that have a screen assembly, 20-60% of those will be replaced.

- The Interior of the tube is cleaned

- The tube is resealed and tested for leaks with a gas spectrometer

- The tube is placed on the vacuum machine. Tubes are evacuated hot, smaller tubes take 12 to 24 hours, and very large tubes can take up to one week.

- The tube is nipped off of the vacuum while still hot. When the tube is fully cooled the vacuum scale is normally around 10-12

- The exterior of the tube is cleaned and replated. Silver for tubes that are socketed and Nickel for tubes that have leads.

- The tube is retested to the manufacturer’s original specification or greater.

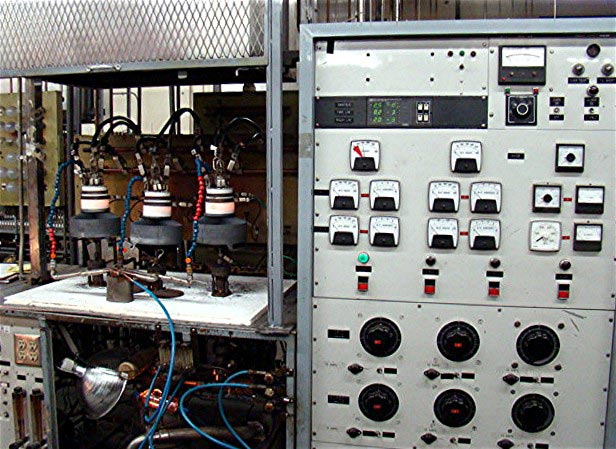

After that, the tube is sent back to its owner or returned to stock. John mentioned that they are very proud of their vacuum tube processing machines, so I asked if he could send along a picture. They certainly look impressive to me, too:

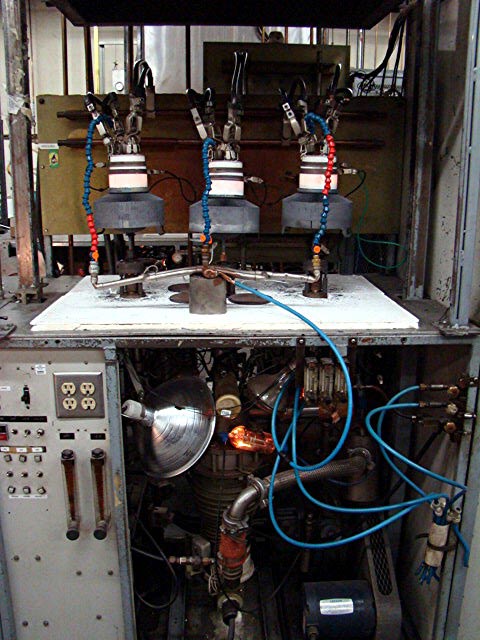

Not exactly sure which tube type these are, but they sure look like 4CX15,000:

Econco has been in business since 1968 and rebuilds about 600-1,000 tubes per month. In the past, broadcasters used most of the larger tube types. However, with the majority of broadcast transmitters shifting to solid state, other markets have opened up such as industrial heating, military, research and medical equipment.